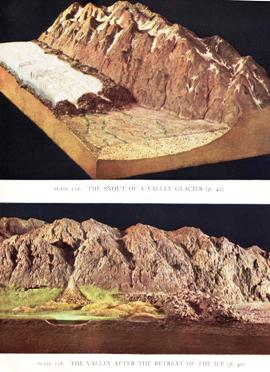

Probably the best-known of his books is Britain’s Structure and Scenery, but for me the true treasure, the book which I now appreciate fired my fascination with geology, was The Earth’s Crust—A New Approach to Physical Geography and Geology. Published in 1951, it was called “a new approach” because Stamp commissioned huge, detailed models of different landscapes—and what lies beneath them—to be made in exquisite detail by Tom Bayley, a lecturer in sculpture, and photographed in colour for the book.

For me, this was magic. I was captivated by the illustrations. I scrutinised the models in detail and even tried, messily, to make some myself. They opened my eyes to how landscapes and their foundations worked, I could look around me on those summer holidays with a different understanding—I could visualise things. And, best of all, some of the models depicted change: for example, the appearance of a glaciated valley when it was still filled with ice and after it had melted (good for Welsh or Scottish holidays! – picture). My curiosity about the world around me was aroused. I was alerted to geology.

The book is, sadly, long out of print and difficult to find; but for me, to open it up today is a deeply evocative and sentimental experience. However, my point here is not simply of sentimental interest: if we examined collectively our beginnings, the things that lured us into geology, could this inform efforts to fire up the imaginations and interest of today’s younger generation? Could we possibly identify comparable ways of “turning on” today’s kids, if not to geology, then science in general?